Japanese and German Medlars: Two Species, One Source of Confusion

There is a fruit whose primary secret lies in patience. Its true flavor slumbers beneath a firm skin and awakens only when the fruit becomes soft and marked by time. This is the medlar. In this article, we recount the story of how the highe...

Author

There is a fruit whose primary secret lies in patience. Its true flavor slumbers beneath a firm skin and awakens only when the fruit becomes soft and marked by time. This is the medlar. In this article, we recount the story of how the highest form of flavor emerges from something most would hastily discard.

Yet the twist is that under a single name hide two entirely different histories—two botanical antagonists, united only by a confusion in nomenclature and their membership in the Rose family. Let us meet this unlikely duo.

The Japanese Medlar (Loquat) — haste and sunlight

The Japanese medlar (loquat, shesek) embodies swiftness and sun. Its fruits resemble apricots and ripen in spring or early summer. They are eaten immediately: juicy, bright yellow or orange, with tender flesh that blends notes of pear, cherry, and a slight citrus acidity. This fruit does not tolerate delay; its season is a fleeting moment of May.

The German Medlar — the philosophy of waiting

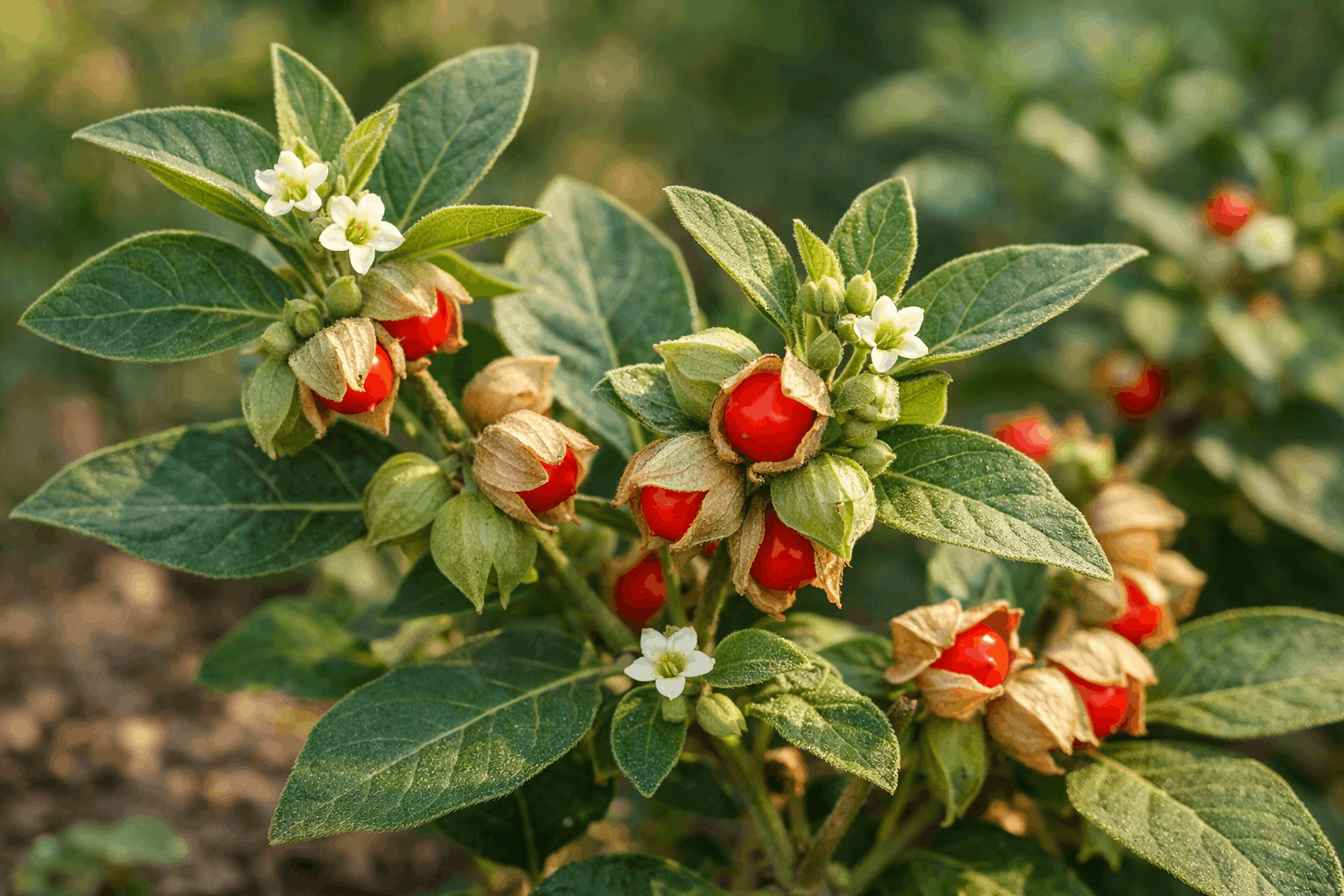

The German (or common/Caucasian) medlar embodies the philosophy of delayed gratification. Its modest reddish-brown fruits are harvested in late autumn, and at that moment they are inedible—hard and sour. Their magic begins later.

The fruits are kept for a month in a cool place until they darken, wrinkle, and soften. Only then, having undergone this internal transformation, do they reveal their true character: deep, cider- and wine-like, with notes of baked apple, quince, and dried fruit. Hence its old nickname—“the drunken berry.”

A Victorian symbol of refined patience

In Victorian England, the German medlar symbolized cultivated patience. After the first frosts, the fruits were laid out in a single layer in fruit cellars—on straw or shelving—and left to rest for several weeks until a mysterious process of fermentation commenced within. Only afterward were they served as a refined dessert. It was the antithesis of instant gratification.

Wherein lies its strength? Nutritional value encoded in the pulp

Despite their external dissimilarities, both medlars are reservoirs of beneficial compounds. Nutritionists describe them as rich sources of polyphenols and antioxidants that combat cellular damage.

Per 100 g, medlars contain:

- Energy: merely 47–50 kcal — ideal for a light snack

- Vitamins: provitamin A (vision and skin), vitamin C (immune protection), B vitamins (energy and nervous system)

- Minerals: potassium (cardiovascular support and blood pressure regulation), magnesium, calcium, iron

- Fiber and pectin: the “sanitarians” of the intestines, improving digestion and aiding in toxin elimination

Their benefits are not abstract; they manifest in specific physiological effects:

- Cardiovascular health: potassium and antioxidants work synergistically to regulate blood pressure and strengthen vascular walls.

- Digestive health: fiber and pectin normalize intestinal function; tannins, particularly from leaves (in decoctions), have been used traditionally as anti-inflammatory agents.

- Immune support: vitamins A, C, and E form a natural barrier against viral infections.

- For women: folic acid is essential during pregnancy, while the fruit’s nutritional matrix may alleviate symptoms of toxicosis and support skin health.

- For men: mineral content—especially zinc—supports reproductive function and prostate health.

In German medlars, up to 0.3% natural alcohol may form during fermentation, hence their “drunken berry” moniker. But one would need to consume an impractically large quantity to feel any such effect.

The other side of the coin: when the medlar is not your friend

Honesty compels us to acknowledge the fruit’s limitations.

- Unripe fruit and gastric distress: this applies particularly to the German medlar. Unsoftened fruits contain significant tannins and acids that may irritate the stomach lining, provoke heartburn, and cause discomfort. During active gastritis, ulcers, or pancreatitis, they are contraindicated.

- Allergic reactions: as with many exotic fruits, unexpected reactions are possible; begin with small amounts.

- Seeds are not edible: the seeds, like those of apples and cherries, contain amygdalin, which may release cyanide compounds in the body. They should not be chewed or eaten.

- Blood sugar considerations: although the glycemic index is moderate, diabetic patients must control portions and consult their physicians.

Culinary alchemy: what to do with this treasure?

The medlar is not merely a fruit to rinse and eat; it is an invitation to culinary creativity.

Japanese Medlar (juicy and tender):

- Fresh: eat as is, peeled or unpeeled — an ideal dessert.

- In salads: pairs well with fruit or even vegetable salads with cheese.

- In smoothies or compotes: adds acidity and density.

- Sauces: puréed with honey and ginger it becomes an elegant accompaniment to roasted meat or cheese boards.

German Medlar (dense and aromatic after fermentation):

- Natural dessert: once softened, it is cut open and eaten with a spoon, like a pudding.

- Preserves: excellent for jams, jellies, marmalades, and fruit butters due to high pectin content. Traditional jams are cooked in three stages to preserve the integrity of the slices and depth of flavor.

- Baking: medlar purée makes an excellent pie filling or sauce base.

A provocative recipe: medlar compote with a nutty accent

Take 250 g of German medlar, 2 liters of water, and 200 g of sugar. Simmer 20–25 minutes after boiling. The secret is that the inedible seeds impart a subtle almond-like bitterness during cooking, lending a simple compote surprising complexity. The paradox: the inedible confers flavor.

The medlar teaches that the most valuable things are not those we seize immediately, but those we allow to mature. That true flavor and character may reside not in glossy perfection, but in ripeness softened by experience.

This is not merely a fruit. It is a philosophy in a peel—a philosophy that may find a home in your garden (the German medlar is frost-resistant) or on your windowsill (the Japanese medlar can be grown from seed as a bonsai). Or it may simply appear one day on your plate, inviting you to taste history, patience, and forgotten genius.