Mirza Alakbar Sabir: A Voice That Cut with Truth

Author

He was the man who, single-handedly, declared war on the hypocrisy, greed, and stupidity of an entire era. Not with a sword, but with a pen—so sharp that the mighty of this world feared it. His verses were memorized and quoted, while he himself was persecuted. Patient by name, as his pseudonym Sabir (“the Patient One”) proclaimed, he showed no mercy in his satire. This was Mirza Alakbar Zeynalabdin oghlu Tahirzadeh—a genius who laughed through tears so that his people might finally awaken.

A Life Groping Its Way: From the Shop Counter to Molla Nasreddin

His life reads like a ready-made dramatic plot. Born in 1862 in Shamakhi to the family of a small trader, he was expected to continue his father’s business. His future seemed predetermined by old patterns: a religious school, a shop, a respectable but unremarkable routine. Yet the young Alakbar “slipped from these hands.” He enrolled in a modern school run by the enlightener Seid Azim Shirvani, a decision that became a point of no return. The teacher discerned a spark in the boy and began to tutor him privately, cultivating his poetic gift.

But the system soon reasserted itself. His father, who regarded his son’s verses as mere whimsy, forced him to abandon his studies and return to the shop. Still, the seed of knowledge had already fallen on fertile ground. By day the young man traded goods; by night he devoured books borrowed from his teacher and wrote poetry.

An aside: to survive, Sabir began writing elegies, congratulatory poems, and funeral odes on commission. It was poetic day labor—but it fed the family.

The irony: the future exposer of hypocrisy began by praising precisely those whom he would later mercilessly ridicule.

An attempt to escape—through pilgrimage and travel in the Middle East and Central Asia—was cut short by news of his father’s death. He was forced to return and shoulder responsibility for a large family. Life in Shamakhi became a struggle against poverty. When his sharp, heartfelt verses—written without charge—began circulating among the people, persecution was added to poverty. An enraged clergy called for a boycott of the poet. Earning a living through poetry became impossible.

Here, however, a turning point occurred. A kindred spirit entered his life—the poet Abbas Sahhat—who convinced Sabir that talent must not be allowed to wither. Their literary evenings became a breath of freedom. In 1903 Sabir’s poems were published for the first time in the Tiflis newspaper Sharqi-Rus. The doors to great literature began to open.

The true ascent came when Sabir met Jalil Mammadguluzadeh and became one of the pillars of his legendary journal Molla Nasreddin. This magazine was the voice of truth for the entire East—and Sabir became its loudest and most recognizable voice.

“Hop-Hop”: The Bird That Awakened a Nation

Working for Molla Nasreddin was dangerous. To protect himself, Sabir employed dozens of pseudonyms. The most famous among them was “Hop-Hop,” named after the hoopoe—a bird whose cry awakens people at dawn and destroys pests. It was a perfect metaphor for a satirical poet.

The secret of his style lay in brilliant simplicity. Sabir effected a revolution by fusing the richness of the literary language with living, colloquial speech accessible to all. People read his poems and gasped in recognition: this is about us, about our mullahs, about the wealthy neighbor! Beneath the apparent lightness lay precise calculation and profound meaning. He spoke to the people about the most complex issues—social inequality, political oppression, international intrigue—and everyone understood him.

A telling episode: persecution did not cease. Once, Sabir—already a poet famous throughout the Caucasus—found himself in such dire need that he was forced to boil and sell soap. When a friend asked how he had come to such a life, Sabir replied with bitter irony:

“We cannot cleanse the inner filth of many people. To cleanse the outer filth, I became a soap-maker.”

In his major work, the collection Hop-hopnameh (“The Book of the Hoopoe”), Sabir said everything he had to say. He lashed out at ignorant fathers who forbade their children to attend school; at greedy oil magnates for whom money had become a new deity; at idle youths who aped European manners while despising their own people. He became the voice of the voiceless—workers, peasants, all who were humiliated and oppressed.

He did not fight religion; he fought falsehood and hypocrisy cloaked in its name. He called for enlightenment and freedom of speech. His satire was a weapon, and laughter—a remedy.

A Legacy That Has Not Fallen Silent

His life ended early—in 1911, at the age of forty-nine. He died in poverty, but unbroken. A year after his death, his satirical monument, Hop-hopnameh, was published and immediately sold out.

Mirza Alakbar Sabir did not merely write poetry. He deliberately awakened consciences, lanced the abscesses of society, and compelled people to laugh at what was painful and shameful. He was that very “Hoopoe” whose cry roused whole generations from sleep. And that voice—filled with truth, pain, and fire—continues to sound today.

-

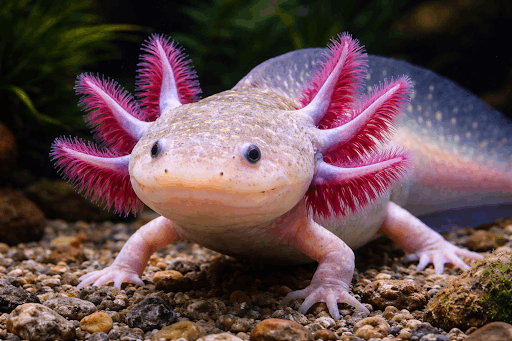

Family LifeThe True Superhero of Nature: The Axolotl’s Regeneration

Family LifeThe True Superhero of Nature: The Axolotl’s RegenerationHe never truly grows up. He reproduces while still a larva. He regenerates lost organs. And he always seems to smile. Meet the axolotl—an organism that has outwitted the rules of biology and bec...

17 Jan 2026, 13:16 -

Family LifeTahajjud Prayer: A Hidden Devotion in the Stillness of the Night

Family LifeTahajjud Prayer: A Hidden Devotion in the Stillness of the NightAmong the many spiritual practices in Islam, the night prayer—Tahajjud—occupies a distinctive place. This voluntary form of worship, performed after the obligatory ‘Isha prayer and b...

17 Jan 2026, 12:49 -

Family LifeMaltipoo — a Dog Designed for Happiness

Family LifeMaltipoo — a Dog Designed for HappinessForget everything you know about dogs — none of it applies here. No service merits, no hunting talents, no noble tomes of pedigree records. That’s a whole different universe. The Maltipoo...

17 Jan 2026, 12:16